So, you think you know a thing or two about Turnarounds? I presume that the answer is yes. Do you think of yourself as a student of adversity? My experience is that most of us who work in the Turnaround realm are. It seems that inevitably, there is always something that will rear up as a challenge no matter how thoroughly you prepare, how closely you follow your plan-to-plan, or how well you adhere to your Turnaround T-minus timeline. The good news is that I have never known a Turnaround not to end. On-time and under-budget Turnaround delivery is (in my opinion) the exception to the rule. Perhaps it is even a myth. And the complete train wreck is of course the other end of the spectrum. Turnaround professionals like to think that the Turnaround Performance Perception Pendulum swings back and forth between Effective and Efficient; however, the reality I’ve witnessed is that the Turnaround Performance Perception Pendulum more often swings between Inept and Incompetent.

What is a Turnaround, anyway?

The vehicle to change the competitive position of an asset and/or the restoration of lost asset capacity.

The Down Side: Plant shutdowns for scheduled major maintenance work are the most expensive and time-consuming of maintenance projects because of the loss of production and the expense of the Turnaround itself. They can be complex; and as the complexity increases, they become more costly and difficult to manage. A plant shutdown always has a negative financial impact. This negative impact is due to both loss of production revenue and a major cash outlay for the plant turnaround and shutdown expenses. However, strategies have evolved over time to negate total plant shutdowns (unless key infrastructure issues need to be addressed) by leveraging value chain decoupling strategies that reduce the footprint of a Turnaround to lesser portions of the plant. A Long-Range Plan orchestrates the sequential timing of the value chain processes over time to stretch out (annualize) the cost impact of maintaining the assets of the entire plant.

The Up Side: Simply put, the benefits are not as immediately obvious, and therefore are often overlooked. The positive impacts are an increase in equipment asset reliability, continued production integrity, and a reduction in the risk of unscheduled outages or catastrophic failure.

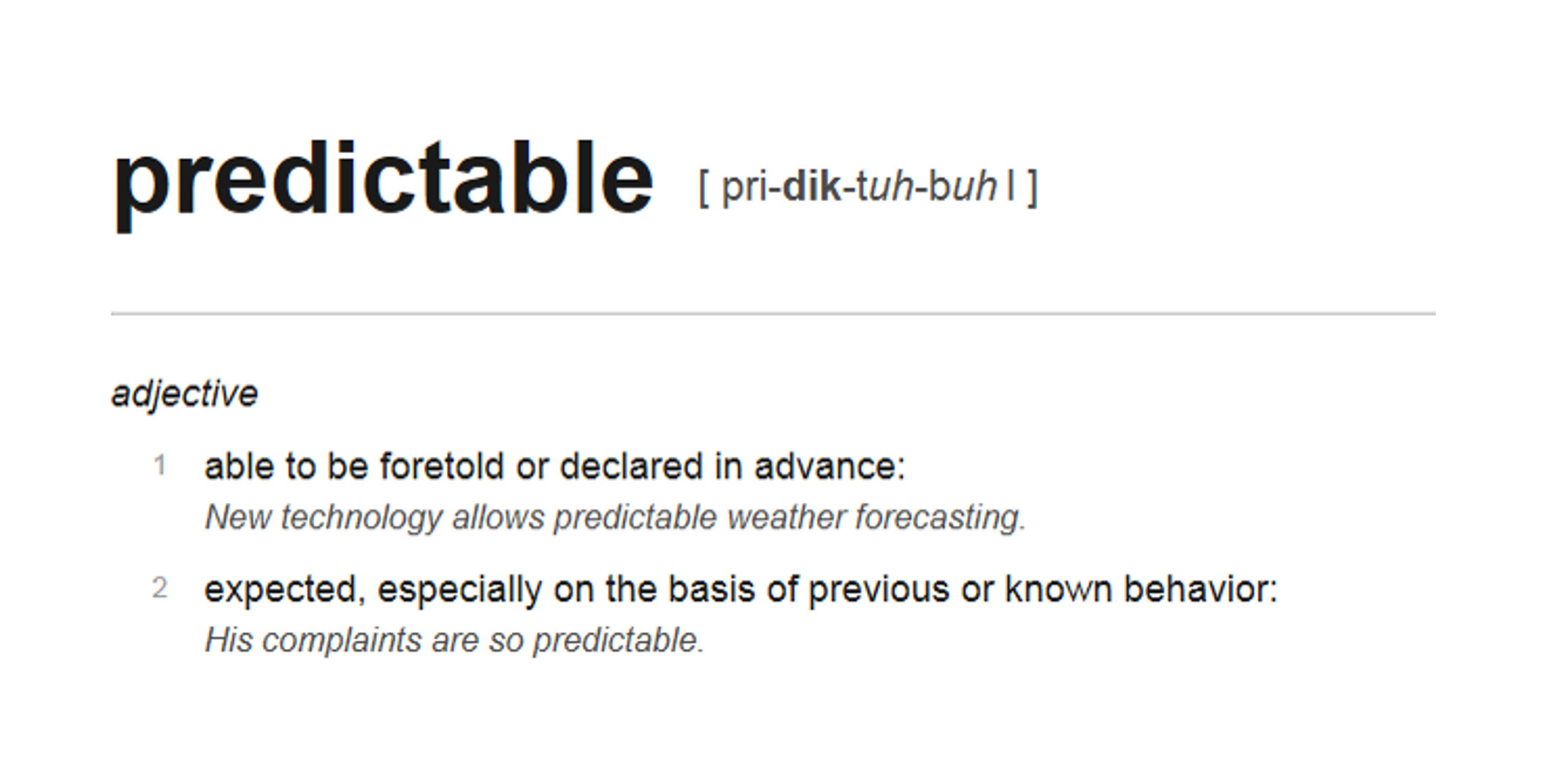

Guiding Principles: If you had to sum up in one word what a Turnaround is all about, what would that single word be? My word is Predictability. Everyone from plant-level to corporate wants to be able to demonstrate that they have their act together and can manage the financial implications mentioned above. Interestingly, one of the most reliable indicators of highly effective Turnaround Teams has been longevity in the job role for its team members – i.e., success is highly people dependent. In the ideal state this should be process dependent, not people dependent. Established processes provide the capability to be consistent despite personnel transitions, which will in turn lead to predictability.

Aside from building the processes that create predictability, the other guiding principal should always be Safety. We all know cost and schedule are at the top of everyone’s mind when planning and executing Turnarounds, but we must never forget that safety is paramount. Keeping safety consciousness at the forefront of everyone’s thoughts is key, as well as establishing an aggressive safety strategy. And you must have belief that working safe is achievable and walk the talk. This takes effort by all. Impossible you might think? I have worked with two separate teams that planned and executed Turnarounds for over six years each without any recordables.

So, what does a best-practice Turnaround process look like?

A best-practice organization typically contains the following:

- A Long-Range Plan (LRP) budget has been established based on the 80% (repeatable) scope basis

“Right Scope” not arbitrarily driven by industry benchmark (i.e., Solomon)

- A consistent, integrated T-minus timeline has been established and continues to be utilized

- A Plan-to-Plan is in place and followed

- A Project Controls Plan is in place and utilized as designed

NOTE: Cost Reporting is not the same thing as Cost Control.

- Appropriate tools are available to perform needed functions: planning, scheduling, site mapping, procurement, logistics, project design, history maintaining database, governance protocols, dashboards, and metrics, etc.

- “Cookbooks” – How-to guides - have been developed for appropriate job roles and people can easily plug into the process.

- A robust/challenging Change Order Process is in place.

Assume the answer is “No” and justify the change inclusion

- A standard reporting process in place, event-to-event, site-to-site

Tailored for distribution to the organizational levels

I suppose that I should elaborate on what a good T-minus timeline should look like.

T-60 – Establish Preliminary Estimate (+/- 50%) Long Range Plan (LRP budget) T-36 – Define Benchmarks & Authorization for Funding (AFF)

T-34 – Define Cost Breakdown Structure T-24 – Submit Authorization for Development (AFD) – Preliminary Scope Validation & AFD1

|

T-12 – Scope Validation & AFD 2

T-9 – Develop Conceptual Cost Estimate - (+/- 30%) This is a Rough Order of Magnitude (ROM) +/- 30% estimate T-4 – Conduct Cost Assessment

– Conduct Schedule Assessment T-.5 – Complete Control Budget This is the amount that the TA cost will be controlled to during execution T+3 – Complete Final Cost Report |

Dealing with Inevitable Challenges

Now it’s time for adversity to kick in. Your vulnerabilities start to surface. Your work process is people dependent, and you have lost a key resource (perhaps even a few). Or your organization struggles to learn from the past despite the “Lessons Learned” exercises that are conducted after each executed event. Once upon a time I sat through a presentation at a conference that really hit home for me. The topic was Lessons Learned. The comment that stuck was “a lesson is not learned until you do something different.” What, pray tell, are you doing different? This is also an important concept to keep in mind when it comes to Safety. After hearing about a near-miss or, worse case, a first aid, what do you need to think about doing differently based on the information that you just learned?

The goal is to plan the work, then work the plan. Start by asking yourself these questions:

- What kind of ownership and accountability do the team members have?

- What percent of compliance to the Plan-to-Plan is acceptable?

- Does the team have low value for process?

- Are the deliverables poor, or do they not even exist?

- Does intimate integration exist between the Plan-to-Plan, HSSE/PSM/PHAs, contracts, bids and quotes (Procurement), Project Controls, Inspection History/Operating Process Variables, Operations, Expense Scope and Capital Projects?

It goes without saying that all of these issues need to be carefully formulated lest your vulnerabilities expose the lack of due diligence.

Scope development is a potential arena for extremely challenging issues, typically resulting from poor or lack of any Scope Control (work scope management being late, incomplete, ever changing). If the LRP budget is based on some ratcheted down previous Turnaround spend you will be in trouble from the start. Scope components that need to be considered are as follows:

- Base Scope (80% Scope) - Scope that should be done in every turnaround to meet the Turnaround Premise

Regulatory inspections are usually Base or Variable scope depending on the required time between inspections.

- Variable Scope - Scope that is routinely performed in turnarounds, but on a differential frequency such as every other turnaround based on unit operations and equipment condition

Regulatory inspections are usually Base or Variable scope depending on the required time between inspections.

- Incremental Scope - One time scope such as projects, equipment replacements, improvements, and repairs

- Regulatory Scope - Subset of scope required by regulation where there is no option not to do

Generally, stems from a governmental entity, permits, insurance requirements, or other binding commitments.

- Where regulatory scope lacks definition or provides options, document the actual requirement separately from the chosen scope of work

- Cleaning Scope - Subset of scope to address fouling and return unit to full rate production

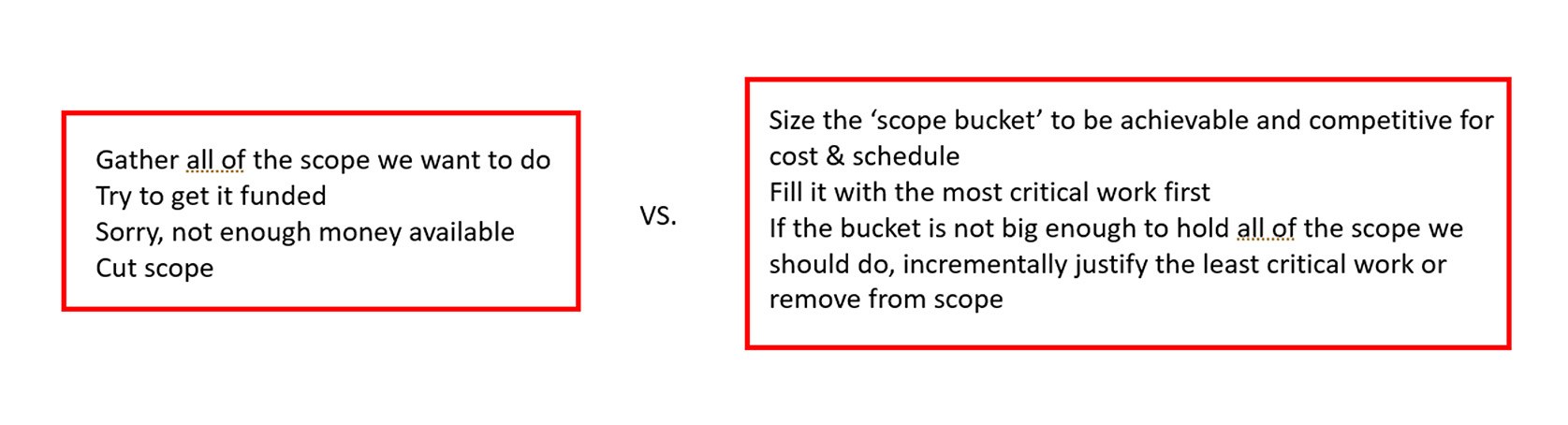

There are two basic scope gathering strategies; 1) fill the bucket then see if you can justify the expenditure and, 2) size the scope bucket to be achievable and competitive. Best practice follows the second option.

In my opinion, Scope should not be considered to be Scope until the entry is a self-standing description that a planner can take out and work with in the field (not a placeholder).

Key principles of good scope gathering:

- Scope collection should be initiated with a well communicated start date and completion deadline

- Each scope item should experience a review/reject process and be prioritized

- The Scope Freeze date is communicated and adhered to as well

- At Scope Freeze all Turnaround scope is vetted and Capital Projects have submitted each project’s Issue for Construction (IFC) package to the Turnaround Team

- All generated scope should have a Reliability Driven Scope Risk Ranking. This provides the starting point format for scope reduction should that be necessary

Pre-empting Common Failure Points:

The additional vulnerabilities of resource availability constraints and Project Process Assurance (or lack thereof) need to be considered. The most common resource constraints are among Operations & Process Engineering. Operations resources are typically the scarcest resource, but their intimate involvement is needed for their activities leading up to Mechanical Start: Shut Down, de-inventory, chemical clean, and hand over for Mechanical Start. Process Engineers are a close second needed for a multitude of tasks while working his/her day job. Project Process Assurance comes under the guise of peer and/or third-party reviews, Stage Gate or Go /No-Go strategy reviews. It is essential to know what the process is and that the process is progressing according to plan. If not, a gap-closure plan must be developed to get back on track.

And to help visualize all that has been previously discussed, there must be metrics – and it’s critical to ensure they’re the right ones -- to help make the invisible visible. Core metrics to ensure thorough and clear progress tracking from my perspective are:

- TA KPIs

- Process compliance

- Cost tracking

- Long Lead tracking

- Component fabrication tracking

- Cleaning and/or offsite repair tracking

- RV testing tracking

- Scope Change tracking (both adding and removing)

- Weld maps and weld bust tracking

- Schedule progress/earned vs. burned tracking

- Cost tracking

- Safety statistics tracking (near miss, first aid, recordable, behavioral safety observation trends)

And the last key component for fending off inevitable vulnerabilities is a robust communication strategy to disseminate information into the organization. Each of the following should have a standard format and appropriate dissemination timetable:

- Management one pager (RLT & TAMT)

- TA daily report

- TA daily Safety Report and a four-panel cost/schedule report

- Core Team “Boardwalk” white board review meetings should be regularly conducted. As an outcome of these meetings:

- Status information should be developed (metrics)

- Gap Identification/Closure Plans, Action Items and a Risk Register should be developed

Putting It All Together:

Although there will inevitably be issues that arise and Turnaround perfection may be a myth, we don’t have to succumb to the Inept-to-Incompetent spectrum. By following these core best practices and embracing process improvements that drive predictability, we can significantly improve both the expectations we’re able to set within our organizations as well as the outcomes we’re able to attain.